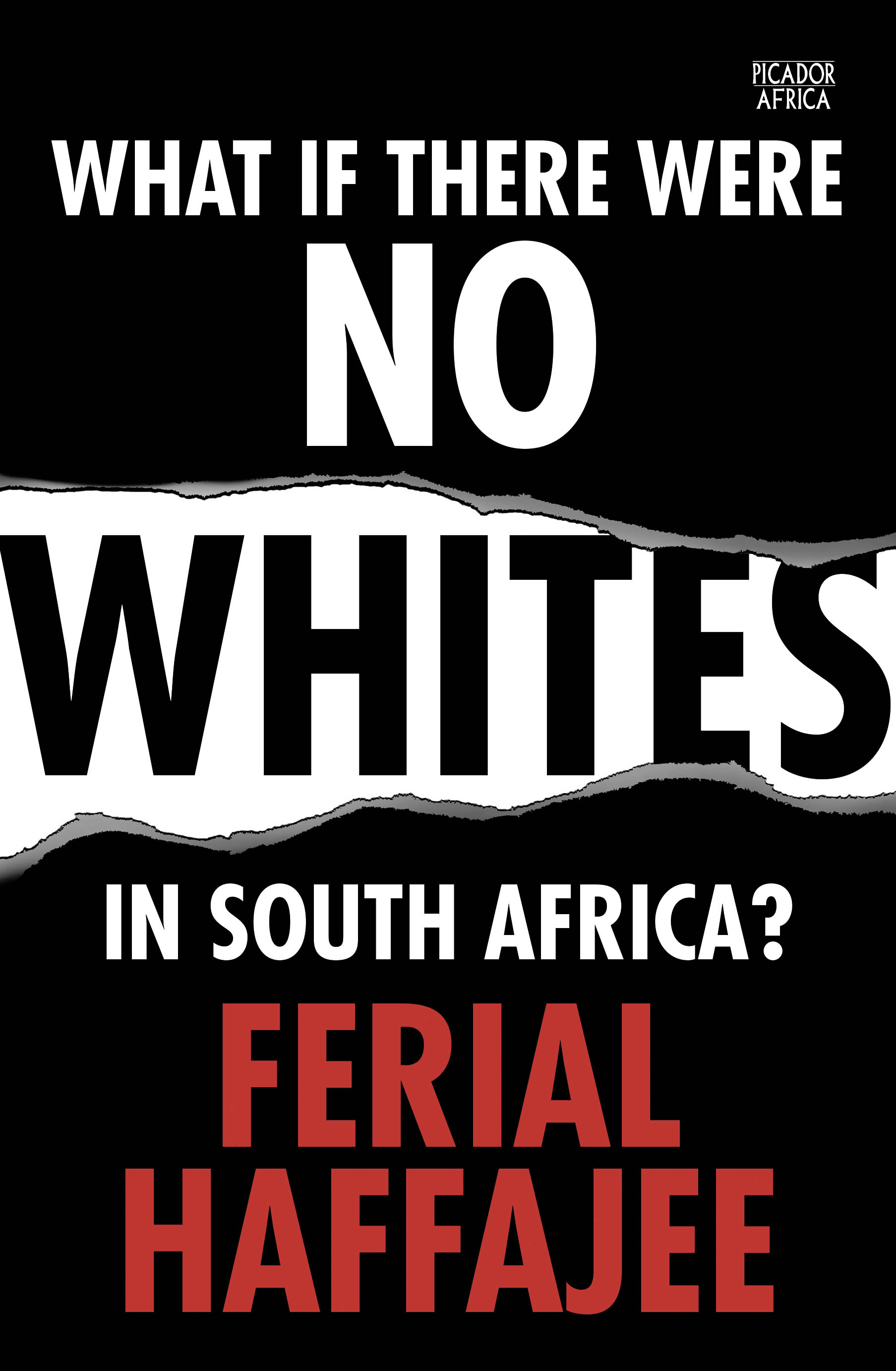

i have just finished reading ‘What if there were no Whites in South Africa?’ by Ferial Haffajee.

And in the shell of a giant big nut, i would recommend it, if only because it tells a different story.

Or rather looks at the same story – that of post-apartheid South Africa – from a different perspective.

It was not exactly what i was expecting in that i don’t really know what i was expecting but as i read it, it certainly wasn’t that.

And i’m pretty sure this would piss off a large number of black friends i am connected to on Facebook and in life.

Ferial describes herself a number of times as naive and that she looks at life with rose-coloured spectacles and there are definitely strong elements of this throughout the book, but i don’t know that that is a bad thing.

What i found really interesting and worth diving into a little bit more was her idea that maybe things are a lot better than we [and specifically the activist community i guess] tend to say they are and she spends a lot of the time backing this up with stories and experiences which i found very helpful.

Journey with Ferial Haffajee

A lot of the book seems to be about her personal journey into understanding and wrestling with concepts of whiteness and white supremacy and then testing those against her personal experience. In the chapter ‘Power is a difficult cloak to wear comfortably’ she makes this observation:

‘Later I sit in on one of the dozens of sessions I’ve attended on media transformation. There, my colleague Stephen Grootes of Eyewitness News says sorry for something and the hall of largely ANC-supporting communicators erupts in applause. South Africa wants the moment of national contrition from white South Africa that our founding father Nelson Mandela did not insist upon when power changed hands. The research I grew so deeply despondent about at the whiteness seminar is precisely what black South Africans need to hear – an acknowledgement of white privilege and its distorting effect on black lives voiced by white people. Acknowledgement is a first step towards action.’

The ‘Better Black’

This concept of the ‘better black’ or needing to adopt a kind of whiteness persona to be more accepted by white people or in white spaces is something i would love to have more conversation about [if you want to guest post on this, message me!] but Ferial touches on that with an encounter with her friend Danielle:

My second realisation is bigger and more formative for me. In my insistence on creating rainbow nation workplaces, what have I suppressed?

Danielle says, ‘When you enter white spaces, [there is] pressure to leave your blackness at the door. Everything that has to do with whiteness has value, [you must] put your blackness in a box to go about your work.’

Like how?

Language. Culture. Values. English is not regarded as a lingua franca but as a fundament of whiteness. Workplace cultures are designed around Anglo-Saxon dominant culture [the firm hand shake, the eye contact, the networks, the practices and ‘codes’ that are acceptable]. Accents.

Danielle recalls her accent changing between her white-school and her coloured home. Her teachers told her to burnish her white accent and to retain it when she tried to push back against how she was being made to sound.

A certain accent can affect how people are treated and perceived. It seems that when individuals live their identities or do not know the codes of working life, it is possible to hear negative perceptions of them – ‘I don’t want that person on my team; they don’t have enough confidence’, is the type of comment reported.

The opportunities available as a result of the pressures of black empowerment might have led to bursaries and opportunities for some young people, but at the same time the pressures to fit into a middle-class life can come at the expense of a sense of social justice; a disconnect in terms of benefiting from a system that is still based on the existence of the under-class.’

B.E.E. Yourself

Ferial speaks positively about the whole Black Economic Empowerment process as she was someone who benefited directly from it. I love how she explains it from her perspective justifying the need for it in the first place:

‘The only reason a generation of us were able to clamber out of one class, out of a distorted destiny, was because of employments equity. From university into the world of work, we gave required help to get a place at the table not because we are ‘stupid’ but because of the structural blocking of opportunity. I am deeply grateful for my place at the table; the opportunities it enshrined have enabled me to live my dreams.

Without affirmative action, I would likely be a retrenched clothing factory worker or a low-level banking clerk. That was the expected, the planned outcome for people like me. The system was called apartheid. We needed help to escape our destiny and millions of South Africans still need that help.

It is not reverse racism, but a constitutional imperative to fix our society. Affirmative action is enshrined in our Constitution. Solidarity, Afriforum and those of you who spammed the Woolies CEO for applying the law are wrong. It discounts, completely, the role of inter-generational privilege in your life.

To make a good future society demands we have make-right policies for the old one. It doesn’t fix itself.

i found this particularly helpful, because i think for the most part the whole B.E.E. thing has been an abstract concept that people have lauded or maligned from various sectors, but Ferial Haffajee puts a face on it and says, ‘This worked for me! It was good.’

When will white people extend the hand?

Ferial tells a heartbreaking story about an energetic young reporter who worked for the SABC at parliament, Tiyani Rikhotso. When he was about 22 or 23 he goes to meet the parents of the white girl he has been dating from Stellenbosch. The meeting does not go well and the father treats him awfully. Here is just a glimpse of the interaction and the affect that it has on Tiyani:

But that appalling one and a half hours he spends at a cold-hearted Stellenbosch Mall being scrutinised and made to feel as if he is not good enough and his relating of it alters my understanding of where we are in South Africa, race wise. It helps me to grasp why a generation is so angry. That man could string together no more than a paragraph of words to sat to the amusing and erudite young journalist who had a thousand young stories to tell.

What Tiyani saw reflected back at him was the view that he didn’t match up simply because he had more melanin than the Stellenbosch man. To have your hand shaken as if you are an untouchable is an awful experience anywhere, but imagine its impact on a young, up-and-coming, newly freed black South African – the uhuru generation enjoying the first years of a wonderful democracy. It must have been like a slap with a damp rag on a beautiful summer day. And it can turn love to hate, making a mockery of the notion of reconciliation, which, to be frank, was always about black people extending the hand, not the other way around.

Sho, that last line though, and the truth of it. This is one aspect of the new South Africa that so many white people miss i think. Especially the can’t-we-just-move-on-already brigade. We do not get how gracious black, coloured and indian people were at the ending of a system designed to treat them as less than human. Too many people thought that cancelling the system’s subscription fee was enough and a get-out-of-jail-free card that was can wave around for the rest of our lives.

the notion of reconciliation, which, to be frank, was always about black people extending the hand, not the other way around.

And white people, for the most part, continue to refuse to extend the hand. Not even engaging in conversations on restitution, land, equity but continuing to forge ahead with a what’s-mine-is-mine, what’s-yours-is-yours attitude.

Ferial adds these paragraphs to the story of Tiyani:

‘South Africa is covered in a patchwork quilt of a million indignities like this that have come to define the experience of a generation of young black people who, I think, are no longer Mandela’s children. They may love our founding president, but they do not accept his legacy of peace and reconciliation among races because of the too many times they have been made to feel inferior and subordinate by old privilege and prejudice.

We all know or see enough mixed-race couples and children to know what happened to Tiyani in that mall is not our only story. As an avaricious consumer of such love stories, I can recite many that would make your eyes burn with sentimentality, or in my case, joy. But in my research, I’ve come to know now that the happy rainbow world I believed was a more generalised experience is a tony contented spot in a vortex of different and painful ones where the hard work of reconciling to life in a country run by a formerly oppressed majority has not been done.’

There is more, but maybe you should just get hold of the book and read it for yourself. As i mentioned it was a lot different than i was expecting, but i enjoyed reading it, if only for the hopeful perspective Ferial Haffajee has for the country’s future in the midst of most of the doom and gloom we seem to get. i don’t think she is suggesting that we have arrived at all, although she would definitely want to counter the narrative that South Africa has not moved all that far since 1994.

This book does not hold up the banner of ‘If there were no whites in South Africa then we would be living in the dark ages cos progress’ but neither does it hold up the idea of having the entire white population marched to the airport and flown to Europe somewhere. It falls somewhere on a different path from either of those two false propositions. We are here together and we need to make it work for everyone. We have made progress, but there is still a lot to be done, both in the hearts, minds and actions of people, but also in systems and structures that tend to keep things the way they are and remind us too strongly of the way they were.

There is work to be done. But also let’s take a moment to celebrate the change that has already taken place as it might be the very thing that gives us the strength and hope to continue moving forwards.

Leave a Reply