It’s been a week since the #MeToo tag went viral. When women across social media platforms started sharing their stories, or simply putting their hands up to help us glimpse the extent of sexual abuse and harassment that so many of them face on a daily basis.

Many of you may have read The Invisible Men piece i wrote, in which one of the main questions was, “Where are the men committing these acts and why is it the women who have had to put their hands up?” You may also have read the follow-up piece i did called So what should we men do with #MeToo?, a lot of which was other people’s thoughts and suggestions of next steps for those of us men realising the extent of the problem.

The danger is that it is a week later and so we move on to ‘The Next Thing’. Which is why i wanted to bring our minds back to #MeToo. We [men] need to realise that this is a systemic and structural thing as much as it is an individual person thing, and that is is rampant. So we cannot just move on.

To that end i read through a number of helpful articles and all the links are provided below the quotes and i encourage you to click through to them and continue with the research yourself, but i thought it might be helpful to have a bit of a highlights package. Some really good and helpful stuff has been written and one of the things we men can do is to take a bit of time to educate ourselves.

Are you aware of the name Tarana Burke?

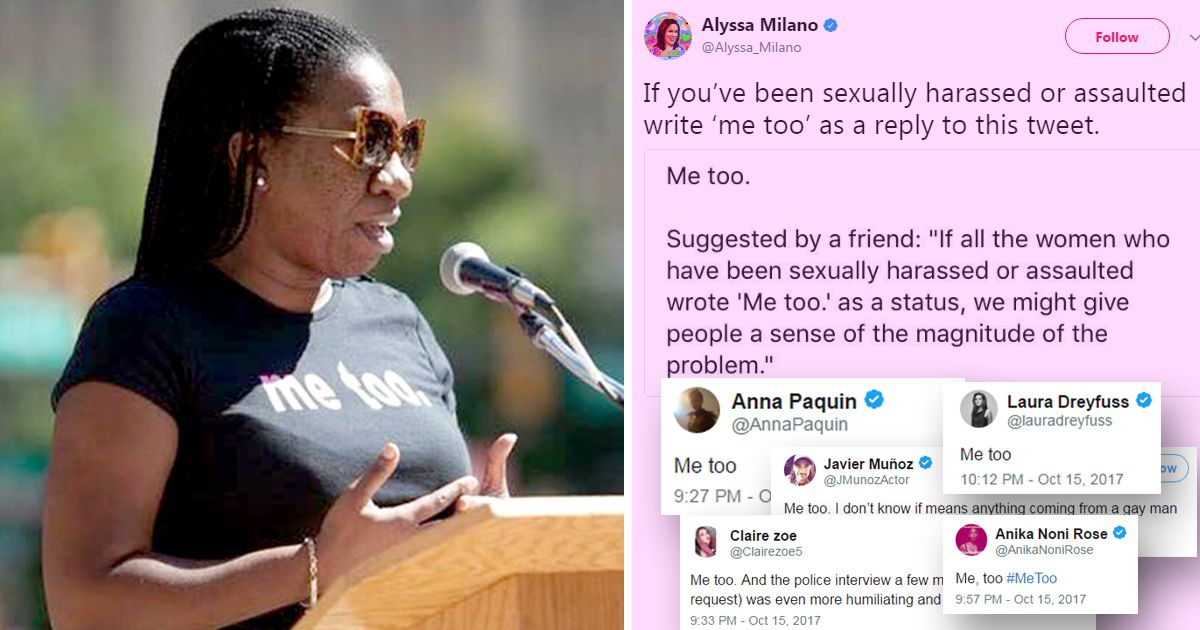

The #MeToo campaign went viral when actress Alyssa Milano posted that now-famous tweet, but did you know that the campaign had actually been started almost two decades previously by a woman of colour? Which is significant. Because there is huge overlapping between the marginalisation of women and that of people of colour and we need to see these struggles as Both/And more than Either/Or. They are both important and both require our attention and vigilance:

It is crucial even in the midst of these feelings that you are not alone to realize that it was not started by a celebrity, Alyssa Milano.

The media seemed slow to wake up to the fact (see edited Salon article here) that “MeToo” was in fact started by Tarana Burke, an organizer and youth worker who is a sexual assault survivor herself. Burke “has been working on “me too” since the mid-2000s — particularly with young women of color — as a means of what she calls empowerment through empathy.”

It is crucial, however, to recognize that this #MeToo campaign to combat violence against women was invented by an African American woman, and then given this exposure by women celebrities.

Never doubt that I believe and have witnessed to the fact that all women’s bodies are vulnerable to sexual violation. But to effectively combat this epidemic, you also need to know, really, deeply, concretely know, that society does not deliver all women’s bodies to this maw of patriarchal assault in the same way.

[Susan Thistlethwaite, #MeToo: See Beyond the Hashtag]

Men, you have to start – and finish – by looking in the mirror

One of the – i’m not sure if failings is the right word – let’s say weaknesses with the #MeToo campaign was that it put the victims center stage which in many cases felt like a sense of reliving their trauma and pain and there was a lot of silence from the ones who are causing the pain and abuse. So it has been helpful to hear a range of voices trying to put the attention where it needs to be in terms of admitting guilt, honestly appraising our complicity in this and calling us [men] to be better:

Clearly, we men have a behavioral problem: All of us. Conservative, progressive. Religious, spiritual-but-not-religious, and even atheist. And if we’re not actively sexually harassing or assaulting women, our ignorance and silence are enabling it. And this general culture of enabling is hurting women (obviously) and is also having negative social and vocational consequences for men who actually care and strive to not treat women like things.

[Mike Morrell: An Open Letter to my brothers in light of #MeToo]

[John Pavlovitz, To The Men on the Other Side of #MeToo]

I’d like to be clear that I understand there is solace for some people in the solidarity of this campaign, in making their experiences public, and I of course don’t begrudge them it, but it seems grotesque to me to lay the burden of representation on women, that we are tasked with performing our pain so often. One of the things I find frustrating about speaking about sexual abuse is that you are expected to play your own history as a trump card. If I object to a rape joke, I’m a sour feminazi, until I explain that I’ve been raped, when I turn into a delicate flower who needs protecting and patronising. There is no room in the discourse for an impersonal non-narrative criticism of the culture.

What is an appropriate response?

It can – and did – feel overwhelming seeing so many #MeToo statuses appear all over Facebook and one of the ways i chose to respond was by clicking an angry emoji every time i saw the status. First and foremost to let women who were sharing know that i saw it and i saw them and it touched me. The decision between crying emoji [i am sad for what you have gone through and go through] and angry emoji [it pisses me off that this happened at all and continues to] was a tricky one, but i eventually settled for the most part on the angry emoji. While it doesn’t mean a whole lot in terms of actually changing anything, i am hoping that the fact that what happened in someone else sparked a strong reaction in me would be some kind of momentary encouragement.

But there were other people offering advice:

[Megan Nolan, The Problem with the #MeToo campaign]

Dr Michael Flood, a Queensland University of Technology Associate Professor who researches ideas of masculinity, had more of the same advice.

“The first thing to say is to believe those women and accept what is really ugly fact, which is that large numbers women do experience harassment.

“There’s a daily dripping tap of sexism and harassment that many women experience and that many men perpetrate.”

He said some men may take comfort in the idea that sexual abuse is perpetrated by only a tiny minority of men, but that idea is false.

“Research shows that in fact large numbers of men do sexually harass or coerce women in various kinds of ways,” he said.

“This is a systemic problem, not an isolated one at all.”

[Me Too: How to respond to a friend sharing their story of sexual abuse]

The wounds of the #MeToo’s are likely ones we have been responsible for inflicting, if not in personal acts of aggression:

In the times we stood silently in the company of a group of catcalling men; too cowardly to speak in a woman’s defense.

In the way we’ve voraciously consumed pornography without a second thought of the deep humanity and the beautiful stories beneath the body parts.

In the times we pressured a woman to give more of herself than she felt comfortable giving, and how we justified ourselves after we had.

In the times we laughed along with a group of men speaking words that denied the intrinsic value of women.

In the times we used the Bible to justify our misogyny.

In the times we defended predatory bragging as simply “locker room talk.”

In the times we imagined our emotional proximity to a woman entitled us to physical liberties.

[John Pavlovitz, To The Men on the Other Side of #MeToo]

Dr Flood said that once men realise the women around them have experienced harassment, there is still a danger they will respond in negative ways.

This can either blame the victim or they can leap in with “paternalistic or chivalric” impulses, such as ‘what can I do to protect women from bad, nasty men’.

Dr Flood suggested it was better for men to look at themselves first.

“We should look at our own treatment of women and the girls we know, at work, at home on the street and make sure we’re never behaving in that abusive, coercive or predatory way.”

Then men should look at the men around them.

“It’s extremely likely every single man in Australia knows a man – a friend, a mate or a family member – who is … behaving in a sexually coercive or harassing way.

“What’s said is that men perpetrating abuse will often listen more to men than they will to women. The one obvious thing to do is say ‘that’s not OK’.

“Say, ‘don’t call out to women or talk about young women in the office in that way’.”

[Me Too: How to respond to a friend sharing their story of sexual abuse]

But at the end of the day, this is on us

What can we do? We need to adopt a #NotOnOurWatch mindset when it comes to these things – from the subtlest forms in terms of comments, jokes and behaviours, to more sinister actions we might see playing out in front of us at a restaurant, bar or club. We need to commit as men to refuse to let this narrative continue uninterrupted.

The problem, really, with all of it is how violently present the victim is forced to be in the narrative, and how utterly passive the perpetrator. The problem is not that women have trouble considering themselves victims of sexual violence, but that men have trouble considering themselves the aggressor. Indeed, it is difficult for all of us to accept how many of the men we know will have committed acts of sexual aggression.

This is why the words “witch hunt” get bandied around at times like this, because it does seem crazy when you start pointing it all out, seems beyond belief really, that so many men are implicated. Because people conflate sexual violence with evil, they don’t identify themselves, or their friends, as part of the problem. Because these acts are specific and contextual, and not always as cinematic as we expect them to be. And there are reasons why they happen, little justifications and excuses to be fed to ourselves. There are always reasons.

[Megan Nolan, The Problem with the #MeToo campaign]

[John Pavlovitz, To The Men on the Other Side of #MeToo]

To my friends, sisters who are sharing “me too”, I believe you, love you, and stand with you.

To my friends, sisters who choose not to share, I believe you, love you, and stand with you.

For every one who shouts, weeps, and whispers #meToo, there’s an abuser who has almost never been held accountable, and a system that perpetuates it. It is up to all of us, starting with men, to uproot, undo, redeem, and replace this patriarchy with something rooted in reciprocal love, respect, and kindness.

Tonight is a night for tears, for listening, and passing the Mic.

[Omid Safi, Facebook]

Mike Frost takes it to a whole ‘nother level when he speaks of the systems and structures and makes a call for pulling down the patriarchy:

It’s not just that our society is male-dominated, or that most of our politicians and CEOs are men. And it’s not just about the gender pay gap and the glass ceiling. These things are symptoms of a more pervasive system called patriarchy.

So the chief characteristics of a patriarchy aren’t just male domination or sexism, but more insidiously, patriarchal societies by necessity became societies of control and separation.

Over generations, this control and separation has seeped into every aspect of society.

We separate from self, from others, and from nature. The fundamental structures we have created over millennia are based on dominance and submission, and the worldview we have inherited justifies these things as necessary to overcome both our basic nature and the natural world (seen as separate from us). We pride self-control and frown on “emotionality”; organizationally we operate in terms of command and control; we treat nature as a thing to exploit, use, subdue, and, most recently, convert to commodities for sale; and often we treat others in the same way.

In other words, patriarchy is the superstructure of human society. We have become so habituated to this state of affairs that most of us don’t even see that it is our own creation.

[Mike Frost: #MeToo: Don’t just say sorry, smash the patriarchy!]

Men, we can do better and we must and hopefully, this is the start. Share these quotes with your friends and maybe even read some of these articles together. Take some time to educate yourself and spend some time listening to the women in your life, if they feel up to sharing their experiences. The idea is not to get them to relive their pain but to try and figure out how you can be an effective ally to them as well as being open to hearing if there is anything in your day to day speech or manner that contributes to the problem.

Have you found any other helpful articles or links that might help us collectively charge forward on this thing? Share them in the comments section.

Leave a Reply